January 20, 2016

Revisiting one of my first Python projects

Revisiting old Python code is always such a treat. Its easy to see what was going on and what the code is actually doing. It is so simple to trace and read, rarely do I ever ask myself

What idiot wrote this?

Only to later find out through a commit or comment that I was in fact the idiot burgeoning genius that wrote it.

Seriously though, use best practices.

Legibility is a legitimate issue and pain point when it comes to programming. If you’re one to hang around programming and computer science websites, classes, and forums, you’ve probably heard of the term ‘spaghetti code’. Spaghetti code is usually code that has been obfuscated (intentionally or otherwise) to the point of illegibility. Some programmers back in the day intentionally turned the art of making spaghetti code into a software pattern and paradigm. They would obfuscate their code and make it a big ol’ digital Gordian Knot (follow that link and learn something new!). And they did all of this in the name of job security. Obviously it became such a problem that other programmers, ones who want to exist in a rational and relatively painless world, came up with several best practices one should follow. The principles behind these best practices were legibility, maintainability, and updatability; code that is easy to read is easy to change. Spaghetti code and procedural coding in general was a big reason why object oriented paradigms came into being. Thankfully, intentionally obfuscated code has been mostly relegated to the history books and certain competitions, such as the IOCCC. It is really clever what some people can come up with, but I thank my lucky stars everyday (and pray) that I never have to deal with a codebase that resembles anything in their competition.

Regardless of what it is, code should always be legible (er, almost always; I’ll make an exception for IOCCC). Programming languages aren’t designed with computers in mind; rather, programming languages act as an interface between a programmer, a computer, and other programmers. Programming languages are primarily a tool for a programmer to functionally and linguistically conceptualize and implement the goal they are trying to accomplish in the digital sphere; secondarily, programming languages are used to communicate with other programmers, either through collaboration on a project, or the act of maintaining an inherited codebase. Computers could care less if you talk to them in Python, X86 assembly, or a punch card.

No really, this is what programming used to look like.

Computers translate everything down to machine code, bits, and binary logic anyway. The most important aspect to a programming language is the human element inherently designed into it. Python lends itself to legibility first and foremost, which lends itself to helping that human element as much as possible.

Some of the most fun I’ve had in programming was in using Python for some dumb project. For those of you who haven’t heard of it, the Python Challenge is a series of programming/thought puzzles that can all be solved with Python. They can be solved with other programming languages as well of course, but the point is, as the name shows, to use and learn with Python. Diving into Python brings back some of what excited me about programming: doing cool things, solving hard problems, and being the master of reality in a digital domain. Turns out I’m more of a peasant-squire than I am a god, but that’s okay.

I overheard a conversation the other day between some people in the CS building at my university. One was raving about Python, and how they started to learn it about a week ago, and how great it is. The other was listening with half an ear, and then said something I wasn’t expecting. He said, and I’m paraphrasing,

Python is a toy language and it isn’t practical. You’ll never do anything useful or enterprise with it.

I was stunned. I’ve always been able to write up a quick Python script to do all sorts of useful things for me. I had a friend win an online contest by scraping some web data, calculating the best answer, and giving it to the contest people; he did all this with Python. I’m not sure what practicality meant in that guy’s mind, but I don’t think we would see eye to eye (the static site generator I use is made in Python!).

With that in mind, I wanted to dig into a program I did about a year ago that I found practical.

My wife, like so many other people, works in an office. And like so many other offices, they don’t have a good way of keeping track of in-office inventory, nor did they have a good way to alert the necessary parties about what they needed. I heard about this, and thought about what I would do in that situation. Being a programmer, I came to the conclusion that I would program a solution.

The libraries I used:

import urllibimport csvimport smtplib

from email.mime.multipart import MIMEMultipartfrom email.mime.text import MIMETextfrom email.MIMEImage import MIMEImageI figured the easiest of accomplishing my goals and achieve proof of concept was to

Those libraries above helped make the rest of the project possible. One of the first libraries I learned how to use was urllib, and what a great library it is. It is super handy for beginner-scraping of web data and metadata.

# We start as usual, retrieving a file with urllib

openSite = urllib.urlretrieve("https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/somerandomgibberishhere/export?format=csv&id", "/home/erick/supply.csv")There is a lot packed into this one little line. I essentially called urllib’s urlretrieve. That method lets me feed it a URL that it goes and grabs. In this case I was able to find out, through some heavy google-fu, that google’s spreadsheet app has an export call that you can use with /export?format=csv&id; essentially I was able to download the file as a file of comma separated values, or CSV. In the above block of code you can see that I not only provide a URL to fetch, but I also provide a place to return/download the file to. So in one fell swoop I hit a url, get a file, and save that file to a specified location. All with one line of code.

Next, I set some values

emptyVals = ['0', 'None', 'none', 'out', 'zero', 'Zero']resupplyList = list()commentsList = list()The first two lines above are ultimately used in sending the email off. The first line specifies who the email comes from and the second one specifies who its going to. emptyVals is an array of strings that the program is going to be checking for. Essentially I envisioned the spreadsheet as being a two (or more) column table, with the first column being the name of the object/office supply and the second column being how much of said office supply was left. I would hope that everyone would write a plain ‘0’ when something is empty, but this hasn’t always been my experience. resupplyList is a list that gets built as the spreadsheet is read. If an emptyVal is encountered, the object name gets added to the resupplyList. commentsList is in a similar vein, however it pertains to a third column, specifically for any additional comments about the office supply.

with open('supply.csv', 'rb') as csvfile:reader = csv.reader(csvfile)for row in reader: if row[1] == row[2] or row[1] in emptyVals: resupplyList.append(row[0]) if row[4] != '': commentsList.append(row[4])

resupplyString = '<br />'.join( supply for supply in resupplyList)commentsString = '<br />'.join( comment for comment in commentsList)This block does a lot for about 10 lines of code. It first opens the file supply.csv for reading as a CSV. It uses the csv library imported at the beginning to read the file. The next uses a foreach or for-in loop to check every row in a column. If a row in the second column is equal to the corresponding row in the third column, or the second row has a value in the emptyVals it appends the name of the supply (in the first column) to the resupplyList. The last nested if-statement is dependent on the one above it, meaning that it only fires when something is empty or has hit the restock threshold. It pretty much checks the 5th column, and if it isn’t empty, it appends it to the commentsList. The last two lines format the list into a string for the email.

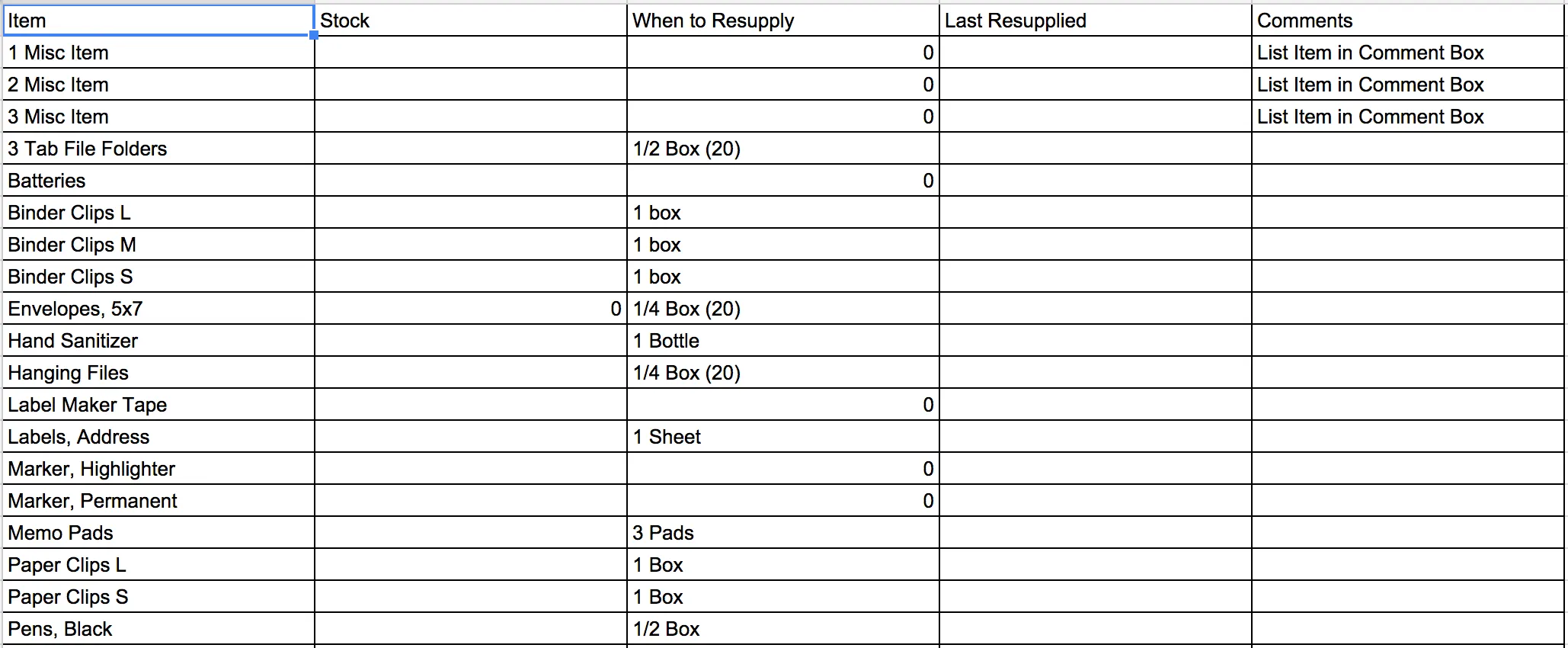

To help visualize, here is an image of the spreadsheet:

msg = MIMEMultipart('alternative')msg['Subject'] = "Supply report"msg['From'] = memsg['To'] = youThese lines are more email building. They set the subject, the recipient, the sender, and the MIME type.

text = "Hi!\nHow are you?\nHere is the supply list you wanted:\n\n" + resupplyStringhtml = """\<html> I had a giant and ugly HTML template here. I'm protecting you by not showing it.</html>""" % (resupplyString, commentsString)Above is the body of the email I had an (actually pretty cool) HTML template that made everything pretty, and would display the items that were missing along with any comments. It was all in a table and laid out with company logos. All the things that bring polish to a project.

fp = open('neslogo.gif', 'rb')msgImage1 = MIMEImage(fp.read())fp.close()

fp = file('paperclip.png', 'rb')msgImage2 = MIMEImage(fp.read())fp.close()

fp = file('idea.png', 'rb')msgImage3 = MIMEImage(fp.read())fp.close()

fp = file('social-twitter.png', 'rb')msgImage4 = MIMEImage(fp.read())fp.close()

fp = file('social-facebook.png', 'rb')msgImage5 = MIMEImage(fp.read())fp.close()This block is for using images inside of the body of my email. I had to open a filestream to these images, set the MIMEtype of the file, and close the filestream.

msgImage1.add_header('Content-ID', '<image1>')msg.attach(msgImage1)

msgImage2.add_header('Content-ID', '<image2>')msg.attach(msgImage2)

msgImage3.add_header('Content-ID', '<image3>')msg.attach(msgImage3)

msgImage4.add_header('Content-ID', '<image4>')msg.attach(msgImage4)

msgImage5.add_header('Content-ID', '<image5>')msg.attach(msgImage5)

part1 = MIMEText(text, 'plain')part2 = MIMEText(html, 'html' )

msg.attach(part1)msg.attach(part2)This part brings everything together. It attaches the images and their headers, attaches the plain strings I have in the email, and attaches the template I created above. This part is the glue. This Stack Overflow answer does a good job of explaining what MIME types are and why we use them.

s = smtplib.SMTP('localhost')s.set_debuglevel(1)s.sendmail(me, you, msg.as_string())s.quit()Finally, I use the smtplib so that the server sends out the mail; I set the debug level to 1 (‘cause I like to see if the email sends), I finally send the email, and I wrap everything up.

The nice part about having this in Python is that I can set it up on a small server instance, set up a recurring cron job, and have it just chug along. It’ll do its thing every week, and another problem was solved.

This is a relatively small program; I didn’t do anything world-changing or magic.

Not everything in programming has to be the next best thing. I’m a firm believer in iterative development in code, skill, and technology as a whole. As long as problems are being solved, I’m ultimately happy. Maybe what I did wasn’t enterprise, and maybe (probably) there is a better way to do what I did. But that wasn’t the point. I wanted to do something fun and practical using a beautiful language.

I did something practical. And fun.

If you’ve read this far, thanks!

Check out the full repo here